Sam Weldon

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

CHAMPAIGN — Marine Cpl. Sam Weldon served in just one World War II battle. It happened to be one of its deadliest.

The battle of Iwo Jima, 70 years ago, ran from Feb. 19 to March 26, 1945. It cost 6,821 American lives and three times as many Japanese.

The battle was 31 days of Weldon’s life. Of his company, which landed with 200 Marines, 34 walked out, he said.

He has just returned from Iwo Jima, Guam, Saipan and Tinian on a trip of 8,800 air miles and 11 days with Urbana’s Ray Elliott of the Marine Corps League.

The Greatest Generation Foundation sponsored the adventure, but the Iwo Jima leg was through Military Historical Tours, the only group the Japanese government permits on the island one day a year for the annual “Reunion of Honor,” and the Iwo Jima Association of America, Elliott said.

Weldon’s not very happy that the U.S. ceded Iwo Jima back to Japan in 1968 after losing so many lives to take it — even if it’s “nothing but a heap of volcanic ash sticking out of the water.”

“But there was no bitterness,” Weldon says of the recent trip. “I felt nothing at times.”

Weldon, 89, was an 18-year-old state champion wrestler in 1943. In football, the Champaign (Central) High School Athletic Hall of Famer was a two-year letterman who led the Maroons in scoring as a senior, and won three letters in track.

He first tried to enlist in the war. His father stopped him, but he still asked his draft board to place him in the Marines.

“You’re crazy,” said the officer who took him in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Looking back at Iwo Jima, maybe the officer was right.

After training in San Diego, he went by ship to Hawaii.

“You never saw so many seasick men in your life,” he says.

From there, it was an amphibious LST to Saipan and then to Iwo Jima.

Weldon landed with the 4th Marine Division.

“I was in the second wave,” he says.

The first wave had met little resistance, he was told. That was because the artillery had softened up the Japanese defense, he learned later.

For him, “the worst day was the first because it was so disorganized,” he says.

His landing on the beach met with immediate action from the defenders.

“I was blown up in the air. It felt like the concussion hit me in the ear,” he says.

To this day, Weldon has deafness that goes back to Iwo Jima.

“I just lost some hearing,” he says. “It’s better than having an arm or a leg blown off.”

A friend had been hurt.

“The beachmaster told me to get a mortar and get going. I just left my buddy where he was,” he says.

On shore, cooks became ammo carriers, so one of the cooks accompanied him up the volcanic rock. At one point, they found refuge in a shell hole.

He saw a Marine with no weapon, a rare sign of cowardice. Near the end of the battle, he saw Marines lighting up smokes in the open — something they were told never to do — only to be hit by hand grenades by the Japanese. He saw the flesh blown off to bare bone on some victims.

“Everybody carried morphine,” he says.

Losses were so heavy that Marines were routinely promoted on the battlefield. Many became officers, then lost their lives.

“We had a lot of replacement officers,” he says.

A body could be booby-trapped. Marines tied ropes around the bodies if they had to be moved and pulled them from a distance.

Relieved by a new unit, he was sent to a troop ship, where the Marines were stripped of their clothes and doused with DDT to kill bugs.

Relative safety did not bring relief. That first night on the troop ship, “you wouldn’t believe the nightmares,” he says.

Weldon’s unit began training to invade Japan, an invasion that he believes would have been disastrous for the U.S. military. On the day the war ended, he was on a long hike.

His group was told they might be sent to China.

Instead, he was sent to Guam and served as a military policemen.

“There were still some Japs in the jungle, but I didn’t see any,” he says. Some of the fiercely proud Japanese soldiers would fight on for years.

Weldon was discharged in April 1946. He remembers “you couldn’t buy a drink if you were in uniform” because of the hero’s welcome.

Back in Champaign, he reconnected with a friend’s sister, Darlene Dowling. They fell in love almost immediately, married and had three children.

Weldon worked for the family business after the war, then pioneered in the pizza business, with places on University Avenue and Hessel Boulevard.

After living in Florida for a while, he became maintenance supervisor for a Champaign apartment complex. He retired in 1987, he says.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Chet Bleich

For the confusion of war, it’s hard to top the Battle of the Bulge, where Chet Bleich and six other soldiers watched the …

Chet Bleich

For the confusion of war, it’s hard to top the Battle of the Bulge, where Chet Bleich and six other soldiers watched the …

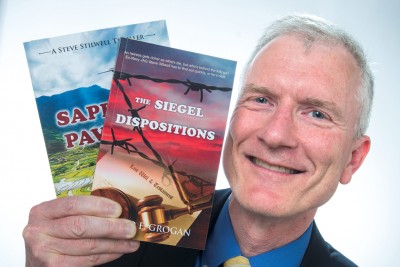

David E. Grogan

URBANA — From blasting Somali pirates with Barry Manilow music 24/7 to working with navies from around the world in the …

David E. Grogan

URBANA — From blasting Somali pirates with Barry Manilow music 24/7 to working with navies from around the world in the …

Fred McCauley

CHAMPAIGN — In September 1952, recent MIT graduate Fred McCauley came to Korea to serve as a forward observer for a mort …

Fred McCauley

CHAMPAIGN — In September 1952, recent MIT graduate Fred McCauley came to Korea to serve as a forward observer for a mort …