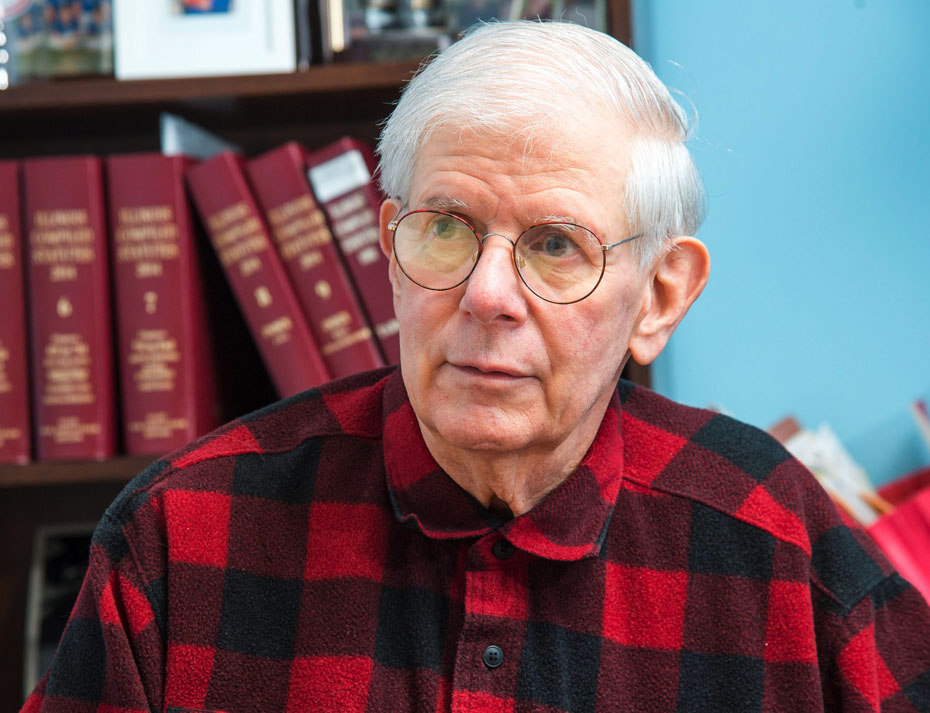

Bernard Puglisi

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

CHAMPAIGN — Bernard Puglisi could easily have avoided serving as a Marine in Vietnam — in fact, he had to appeal a medical discharge after completing advanced, and dangerous, aviation training.

Puglisi, 72, a Champaign attorney, served five years on active duty and four years as a reserve officer, reaching the rank of major.

But his career nearly ended early when doctors diagnosed a rare blood disorder when he fell ill after a high-altitude flight.

“They said I should never have been on active duty,” he recalls.

After an extensive effort to stay in the Marines, including board appeals, Puglisi was allowed back on active duty, but not as an aviator.

He spent his last year on active duty in Vietnam using what he learned in flight school to help coordinate ground troops and jets near Danang.

He grew up in upstate New York, studied Asian history in college and volunteered for the Marines.

“I didn’t want to be drafted. I wanted to be out with the best in the field,” he says.

Puglisi hoped to be an aviator, because he’d caught the bug for flight as a young boy.

“The Marines were a fascinating and unpredictable experience,” he says. “I started out in aviation, the flight officer program. I flew the T-34, and the next aircraft was the T-28, known as the ‘ensign killer.’ It was almost the Puglisi killer.”

His unit sped through the training process because so many aviators were being lost in Vietnam that there was an urgent need for replacements.

But that sped-up training also cost lives, including a 1967 crash that killed three of his seven classmates.

Puglisi said flight training was a dangerous but rewarding experience.

“The fun thing about aviation is it’s very challenging and it’s an education in a lot of different things: avionics, electronics, aerodynamics; that was one of the attractions,” he said.

“You wind up memorizing every plane you go into. That training builds confidence.”

Working against that confidence was an instructor nicknamed “the screamer” who would shout insults over the intercom or make the plane shake, “basically trying to make you quit.”

Puglisi was assigned to learn to be a bombardier/navigator.

He wound up in the A6 Intruder, a state-of-the-art jet, in the right seat.

But soon after that came the diagnosis of the blood disease.

His commitment to the Marine Corps was coming to an end, but he felt the need to serve overseas, so he added a year.

Puglisi was assigned primarily to Marine Air Support Squadron 3 from April 1970 to April 1971, working for some time directing fixed-wing aircraft in conjunction with ground troops.

Hill 327 got its rather unimaginative name from being 327 meters above sea level.

From Hill 327, “you had a great view of the war, especially at night,” he says. “We had the big picture. We knew where all the flights were.”

Its electronics helped guide planes from being hit by ground fire while often serving soldiers on the ground. Other officers worked with helicopters, which Puglisi described as key to the war effort.

“We didn’t want aircraft flying through artillery barrages or naval gunfire,” he says.

While he was in Danang, he took the law school aptitude test — there’s a photo of him from that very day that’s on the Internet.

After active duty, he earned a law degree from John Marshall Law School. After a year in the Vermilion County State’s Attorney’s office, he went to work for the city of Champaign.

In his law practice, he met a law student, Mary Gorski, and they eventually married and had two children. They practice law out of the same office today in Champaign.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Larry Soliday

URBANA — Larry Soliday served in an elite unit that did everything from helicopter rescues to fighting in enemy tunnels. …

Larry Soliday

URBANA — Larry Soliday served in an elite unit that did everything from helicopter rescues to fighting in enemy tunnels. …

Raymond James

RANTOUL — Raymond James’ early World War II training involved some mule-headed comrades. The 97-year-old Rantoul residen …

Raymond James

RANTOUL — Raymond James’ early World War II training involved some mule-headed comrades. The 97-year-old Rantoul residen …

Franklin Longfellow

CHAMPAIGN — When Franklin “Frank” Longfellow returned from Vietnam, his entire welcoming party was two students from Cen …

Franklin Longfellow

CHAMPAIGN — When Franklin “Frank” Longfellow returned from Vietnam, his entire welcoming party was two students from Cen …