Bill Clemens

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

CHAMPAIGN — On the fiercely contested island of Okinawa, Bill Clemens served as a Navy medic, close enough to the lines that snipers fired at Marines and medics all around him.

“I don’t know if they were firing at me,” he says. “They didn’t hit me.”

At other times, the Americans took to the caves as makeshift air raid shelters.

Clemens, 90, was a pharmacist’s mate in World War II, supporting the Marines as they took islands back from the Japanese, and as the war neared its end, on a ship headed to invade Japan’s mainland.

Okinawa produced thousands of casualties on both sides, and hundreds a day came into his evacuation camp for more than a month, he recalls.

“We were trying to save the men that had been patched up at the front lines,” he says. “There were a lot of terrible wounds.”

He did everything from bedpans to sutures, Clemens recalls.

“Anything that needed to be done,” he says.

Some of it is too hard for him to talk about.

Growing up near Chicago, he enlisted in the Navy right out of high school in 1943, along with most of his friends.

Taught suturing and other skills in a Navy base in Kansas, of all places, he was in the Pacific before the end of the year.

After Guam was retaken in July 1944, Clemens was based on the island. From there he traveled on an LST to Okinawa, the southernmost prefecture of Japan.

In a battle that lasted 82 days, there were a thousand casualties a day, counting both sides. Even thousands of civilians were killed.

The evacuation hospital never shut down day or night.

“We slept when we could,” Clemens recalls. He was with the Marines on the north side of the island, while the Army took the south.

So unrelenting was the fighting that military planners feared that invading mainland Japan could cost millions of lives on both sides, including civilians ordered to fight to the death.

But the invasion had to happen, the generals and admirals told their soldiers, Marines, sailors and airmen — only a handful knew that the atomic bomb was being created in secret labs spread out over the nation.

So Clemens had no way of knowing, within a few days of reaching Japan, that he was about to get a reprieve in the form of two massive bombs.

Like others interviewed by The News-Gazette, he has no reservations about use of the bomb.

Wife Mabel is in complete agreement. “If there hadn’t been Pearl Harbor, there wouldn’t have been the bombs,” she says, subject closed.

Only miles off the coast, Clemens’ ship was diverted to Tientsin (now Tianjin), China. He was sent home for leave, then back to Guam.

Even after the war, there were fatalities. Clemens remembers a soldier who had gone into a cave to destroy munitions, only to be badly burned.

He died on the table, the pharmacist’s mate recalls.

Back home, Clemens wound up at Bradley College (now University) in Peoria, where one of his jobs to pay tuition was at Hyster.

He used his education degree to become a trainer for Hyster, which sent him to Georgia. There he bought a house with Mabel, and almost immediately was transferred to Danville.

The plan was to retire in Champaign and baby-sit the grandchildren, but the four Clemens children all moved out of town with the eight grandkids.

So he lives happily in a house full of art with Mabel, whom he met on her porch when he was out with a friend in Kansas in 1943.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

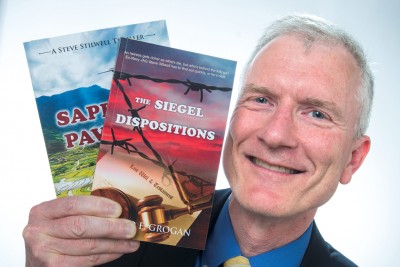

David E. Grogan

URBANA — From blasting Somali pirates with Barry Manilow music 24/7 to working with navies from around the world in the …

David E. Grogan

URBANA — From blasting Somali pirates with Barry Manilow music 24/7 to working with navies from around the world in the …

James Paul Lafary

PAXTON — James Paul Lafary stayed on the ground, but saved many bomb crews from crashing after they came under attack. T …

James Paul Lafary

PAXTON — James Paul Lafary stayed on the ground, but saved many bomb crews from crashing after they came under attack. T …

Harold Thomas

PHILO — Harold Thomas saw a kamikaze plane up close as it rammed into the USS Idaho, and survived with only some hearing …

Harold Thomas

PHILO — Harold Thomas saw a kamikaze plane up close as it rammed into the USS Idaho, and survived with only some hearing …