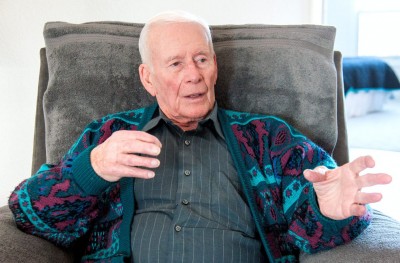

Robert Alsop

By Paul Wood

Photo By Heather Coit/The News-Gazette

CHAMPAIGN — At an outpost that could have been overrun any minute by the smallest of North Korean forces, Robert Alsop was part of a unit that spied on the country that it was still technically at war with.

In 1955, an armistice had only been signed two years earlier on the Korean peninsula, America’s least-resolved war.

A Champaign High School graduate, after working a couple of years in construction, Alsop had enlisted in the Army’s security branch to avoid being drafted in the infantry.

“The FBI came around asking my friends about me, because I would be getting a top-secret security clearance,” he says.

One of 11 children, Alsop had lost a much older brother in the first days of the Japanese invasion of the South Pacific, a brother in the Korean War and another brother who was a Marine in World War II.

Alsop left as the equivalent of a staff sergeant.

Now 81, he remembers what it was like to serve in the Cold War years.

The lowlight: 14 days on ship from Seattle to Japan before flying to Korea. “I’m glad I wasn’t in the Navy,” he says.

“The highlight was my time in Korea. I was in the Army Security Agency and we did some very good things, such as intercepting North Korean messages, triangulating North Korean radio centers and running spies into North Korea,” he says.

Alsop served in the Army from 1955-57 in Korea, just north of the decisive 38th Parallel, with 15 or 20 men, only one of them an officer, at a radio outpost near the Demilitarized Zone.

“There was a lot of tension at that time. We were stationed in a small outpost in what used to be part of North Korea, and it was always a tense time, even though there was no combat at the time,” he says.

“We had a few carbines and pistols if they ever decided to attack us,” he recalls.

The outpost was on the east coast; the nearest friendly village was Sokcho, but the troops did not venture there. He only left the outpost for rest and recreation in Japan.

Instead, supplies usually were flown in. If the plane could land, things went smoothly, but sometimes mail had to be dropped by parachute.

For many things, though, Alsop says the outpost was generally self-sustaining. There was a generator for power. A pumping truck was ready to suck fresh water out of a nearby stream, he says. They could travel to an Air Force base for food.

Alsop was trained in Morse code, to send and receive messages, and to intercept messages from the north.

Cryptographers had the difficult task of breaking code that was originally written in Korean. The Army badly needed linguists who could handle the task.

Another part of the unit used radio direction finders to look for North Korean transmitters, a job Alsop did on a few occasions.

And others sent spies into the north. He believes they were recruited from South Korean volunteers.

Alsop wasn’t allowed to discuss any of this for several years after he was stationed on the peninsula, since the operation was top-secret.

But he’s quietly proud of his service.

Alsop took an Honor Flight to the nation’s capital in 2015.

He married Carla; between them, they have six children. He worked for Illinois Power until retirement, but didn’t use a radio on that job.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Ray Heckler

URBANA — With a shell-shocked soldier for a companion, Ray Heckler drove a Jeep near the Rhine River as shells landed al …

Ray Heckler

URBANA — With a shell-shocked soldier for a companion, Ray Heckler drove a Jeep near the Rhine River as shells landed al …

Paul Wisovaty

TUSCOLA — Paul Wisovaty entered the Vietnam War as a John Wayne fan, but after six months “in country,” began to notice …

Paul Wisovaty

TUSCOLA — Paul Wisovaty entered the Vietnam War as a John Wayne fan, but after six months “in country,” began to notice …

Bon Bui

URBANA — Wounded six times in battle, Major Bon Bui spent 13 years starving in a prison and being “re-educated” in commu …

Bon Bui

URBANA — Wounded six times in battle, Major Bon Bui spent 13 years starving in a prison and being “re-educated” in commu …