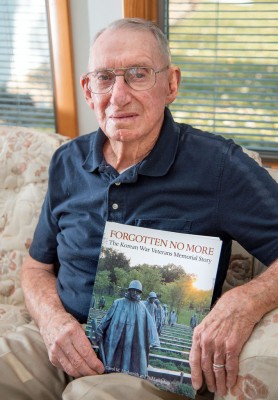

Kenneth Dugan

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

PESOTUM — During the Korean War, Staff Sgt. Kenneth Dugan worked midnight shifts watching for “bogies,” unidentified planes over the sea between Korea and Japan.

The Air Force veteran, 81, has performed a lifetime of service, including on the Illinois State Police, the University of Illinois Fire Department and the Champaign City Council.

Growing up near St. Louis, Dugan was working in a glass factory and facing the draft when a buddy told him that he was heading out to enlist in the Air Force.

Dugan knew he’d rather enlist than be drafted. What he wanted was the Navy.

He told his friend he’d go along with him.

“But the Navy recruiter wasn’t there that day,” so Dugan ended up enlisting in the Air Force.

The Air Force farce didn’t end there.

Dugan wanted to work as a heavy-equipment operator. Instead, the service decided he had technical skills that would make him a great radar operator, back when controllers wrote updates on Plexiglass screens.

He ended up serving on an Aircraft Control & Warning site on the Chiba Peninsula, near Tokyo. He could see Mount Fuji, but never traveled there.

“Now I wish I had gone,” Dugan said.

He was not on a base, but an early-warning site.

“We monitored flights entering our airspace and identified them according to filed flight plans,” he said. “We had several bogies. Those unable to be identified were assumed hostile, and we scrambled fighter planes and controlled them to intercept unknowns.”

Sometimes he did midnight shifts that were simply boring, he said.

The radar crews usually worked six hours on, six hours off for seven days, then had three days off. AC&W crews also assisted fighter squadrons by directing them in practice intercepts.

“We sent out seaplanes to guide some planes in,” he said,

If they had to ditch over the ocean, they would be close, so the seaplanes could rescue them.

During massive operations to test the systems, so many jets flew that it was almost impossible to keep track of them, Dugan said.

He was also detailed on special classified missions to check on equipment, at one point eight days overhauling a weak link in the defense grid.

The pilots faced serious dangers, he said. In radio transmissions, Dugan heard one pilot talking about low clouds, which another pilot warned were actually snow-capped hills.

Another time, a pilot passed out from lack of oxygen and his wingman desperately tried to wake him on the radio.

Dugan spent two years in Japan but was able to leave his site for military-police duty — “to make sure everybody was behaving themselves,” or on courier duties.

Once, he was with an officer when their Jeep got a flat on a “cow pasture road” and the spare’s lugnuts turned out to be welded to the side.

“I had to walk a while to find a house and then try to make the Japanese understand I needed to use the phone, then work through the Japanese phone system to report it,” he said.

After the war, he worked less than a year for the Illinois State Police when it had headquarters on University Avenue in east Urbana.

He served nearly 30 years as a firefighter for the University of Illinois fire department, retiring as a battalion chief.

He and wife Jean have three children.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Jim Voyles

TUSCOLA — In the Vietnam jungle, Jim Voyles might have been within 50 feet of the enemy and not seen him through the bru …

Jim Voyles

TUSCOLA — In the Vietnam jungle, Jim Voyles might have been within 50 feet of the enemy and not seen him through the bru …

Stanley Gilles

CHAMPAIGN — Even though Stanley Gilles worked three years for Illinois Bell as a lineman before he was drafted to Korea, …

Stanley Gilles

CHAMPAIGN — Even though Stanley Gilles worked three years for Illinois Bell as a lineman before he was drafted to Korea, …

Jim Morris

CHAMPAIGN — Sgt. Jim Morris endured “gruesome” scenes investigating war crimes in Kosovo. A rock thrown at his vehicle t …

Jim Morris

CHAMPAIGN — Sgt. Jim Morris endured “gruesome” scenes investigating war crimes in Kosovo. A rock thrown at his vehicle t …