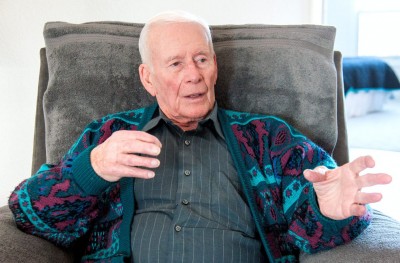

Ted Sandwell

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

URBANA — The government thoughtfully issued Marine Cpl. Ted Sandwell sunglasses before setting off a nuclear bomb just 3 miles away from his trench in 1957.

Cover your eyes, he was told.

“I could see through to the bones in the arm,” says the Urbana man, who is turning 79 and somehow hasn’t suffered bad health effects as a result of the blast.

The bomb was Test Shot Hood, part of Operation Plumbbob in Nevada, a series of tests that have been linked to thyroid-cancer deaths among veterans.

The purpose of the test, Sandwell recalls, was to see if soldiers could rise from the trenches after a bomb drop and fight the overwhelmed Soviets or Chinese — a prospect that now seems unthinkable.

Test Shot Hood, on July 5, was the largest atmospheric test to take place in the continental U.S. — and was later revealed to be a hydrogen bomb, an explosive many times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Sandwell said the blast was followed by a rebound that knocked the helmets off the Marines and other military personnel.

He was a monitor, assigned to check the men with a Geiger counter. Most of them were mainly worried about nearby trucks that were supposed to take them to Las Vegas after the test, he says.

Pilots flying near Hawaii could see the glow of the blast, Sandwell says. When he talked to a doctor about it, the physician said Sandwell’s exposure was equal to millions of X-rays, yet somehow left no apparent effect on him.

“It was the dirtiest test stateside in terms of radiation fallout,” R.J. Ritter, national commander of the National Association of Atomic Veterans, told the Orange County Register. “And they walked about 2,200 Marines right into ground zero.”

Similar tests were blamed not only for cancer deaths among veterans, but even the cast and crew of a John Wayne Movie, “The Conqueror” — including The Duke himself.

It was John Wayne who’d inspired Sandwell to join the Marines after he watched “The Sands of Iwo Jima,” in which Wayne was a tough-as-nails Marine sergeant.

By the time Sandwell was a Marine, it was 1954, and he was sent to the de-militarized zone in Korea, where the war was supposed to be over.

But the de-militarized zone was not properly de-militarized.

“The shooting was still going on,” he says. “The Chinese told us over loudspeakers that they hadn’t signed the peace treaty.”

So when the Chinese weren’t playing “The Tennessee Waltz” for the Americans, there was a chance they’d be plunking off shots.

A military list of 1954 American deaths in Korea includes sniper deaths as well as hostile-caused plane crashes.

After a couple of months in the DMZ, Sandwell was transferred to ship duty, where the Navy watched for signs of Chinese trying to move beyond the DMZ on the Southeast China Sea.

After Korea, Sandwell was a battle engineer, manning a Caterpillar bulldozer, before his first service as a trained atomic, biological and chemical monitor. He was present at another test, a bomb that turned out to be a dud, Shot Diablo.

Sandwell returned to central Illinois after his service.

A Philo native, he had a farm there, but spent most of his career in trucking.

Sandwell’s last assignment was driving trucks for country duo Brooks & Dunn. He only retired when they did, in 2010.

He and wife Mary, married for 34 years, have six children between them, and eight grandchildren.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Ray Heckler

URBANA — With a shell-shocked soldier for a companion, Ray Heckler drove a Jeep near the Rhine River as shells landed al …

Ray Heckler

URBANA — With a shell-shocked soldier for a companion, Ray Heckler drove a Jeep near the Rhine River as shells landed al …

Bon Bui

URBANA — Wounded six times in battle, Major Bon Bui spent 13 years starving in a prison and being “re-educated” in commu …

Bon Bui

URBANA — Wounded six times in battle, Major Bon Bui spent 13 years starving in a prison and being “re-educated” in commu …

Gary Volkening

MAHOMET — In Vietnam, a sniper bullet passed through Gary Volkening’s wallet while he was sleeping in a hooch. “This is …

Gary Volkening

MAHOMET — In Vietnam, a sniper bullet passed through Gary Volkening’s wallet while he was sleeping in a hooch. “This is …