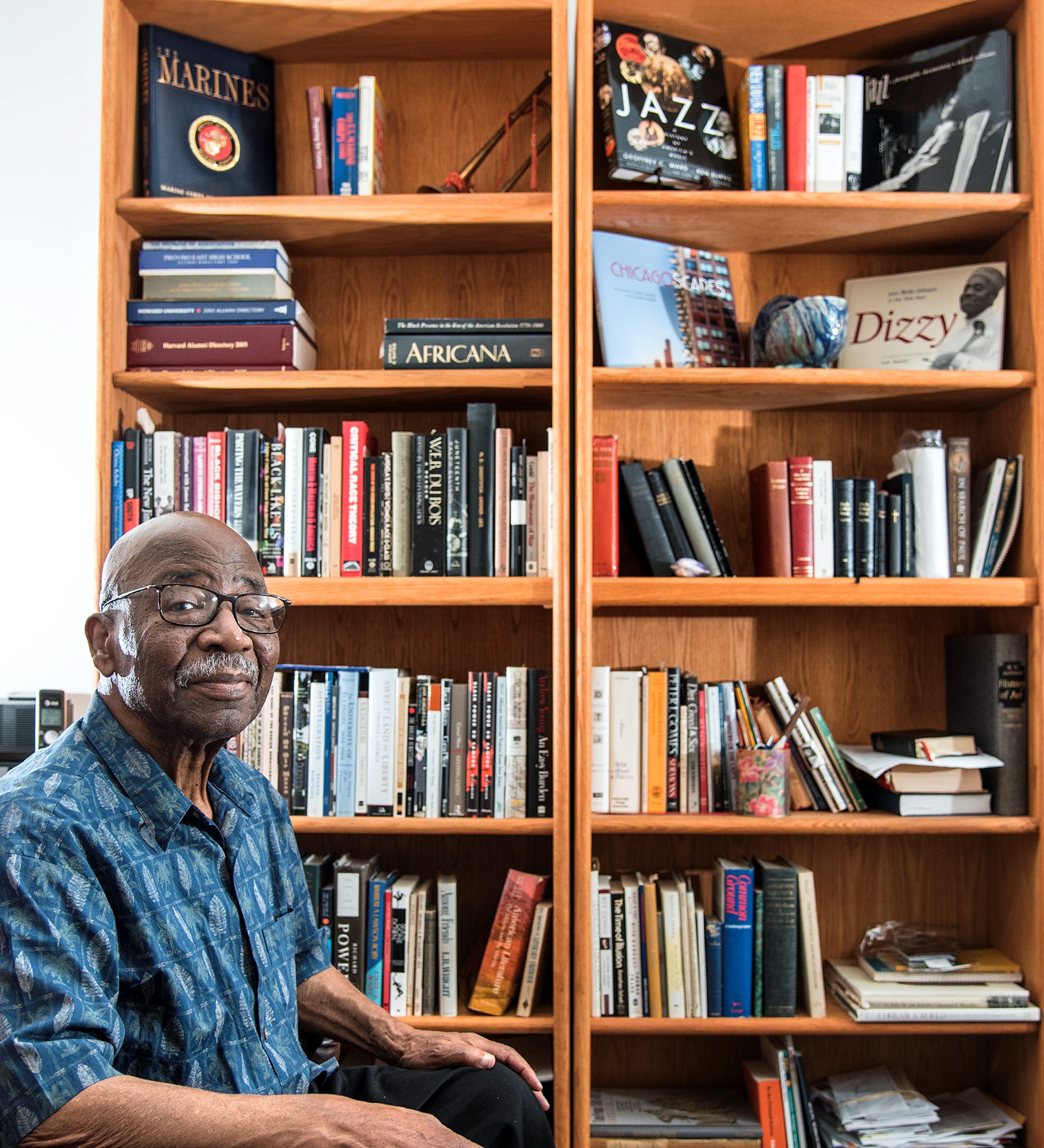

Joseph Smith

By Paul Wood

Photo By Heather Coit/The News-Gazette

URBANA — Talk about being caught between a rock and a hard place.

Marine Cpl. Joseph Smith was sleeping in a depot with tons of ammunition and barrels of airplane fuel on Okinawa in 1945.

On one side: the air base, where planes took off every morning to bomb Japan. On the other: a harbor full of American ships.

“There was lots of shooting. Bedlam. We were behind the lines perhaps a mile, and there was constant fighting,” recalls Smith, now 91 and living in Urbana.

“Sometimes we were mostly afraid of being shot by a nervous Marine,” when the sirens went off and word came that the Japanese had broken through the lines near the air base.

The Japanese knew they were losing World War II, and their efforts had quite literally become suicidal — kamikaze planes where the pilot took off with no hopes of returning alive.

“It seemed like every night. They would take any target they could get, preferably a ship or a group of bombers,” he recalls.

“We hoped they were good at their job,” he joked, because an ammo dump could also be very attractive if it was impossible to get a ship.

Smith was in his bunk when a bomb smashed into a fuel dump.

“Barrels of 100-octane airplane fuel blew up,” he says. “The barrels were flying in the air. Pow!”

Only one man was wounded, and he only got a scratch. Smith’s fellow Marines joked about the easy Purple Heart.

Born in Illinois, Smith grew up in Boston and still has something of a Harvard accent he earned the hard way.

With a bachelor’s degree from Howard University and a master’s from Harvard with a specialization in the American novel, Smith taught in Michigan before the University of Illinois.

The GI Bill paid for his education and gave him a career, so he still bristles when he hears people complain about “big government.”

Smith began his career at the UI in 1964. In 1978, he was named assistant vice chancellor for academic affairs, director of affirmative action and associate professor of English.

But he was only one year out of high school when he was about to be drafted into the Army in 1943. He figured he’d be a truck driver; there weren’t many options for black soldiers.

A Marine recruiter pulled him out of line.

“Joseph Smith, you’re just the man I’m looking for,” he said.

The recruiter told him that Smith’s high school degree made him something special, and that the Marines could find a place for him.

Smith knew the Marines were part of the Navy, and the Navy would probably use him as a cook. But he hoped the Marines would give him something else to do.

“I wasn’t savvy enough to ask about integration,” he said. “Contrary to my Boston way of life, these were Southern mores.”

He was sent to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, where black men had their own barracks. There was punishment duty, such as standing at attention at night in civvies — underwear — while mosquitoes made a meal of them.

From New Orleans, they were shipped out on an LST, a very small landing craft, to New Caledonia, then Guadalcanal, newly taken back by the U.S.

“The trip took months,” he says.

Smith was at Okinawa until the war ended. Like others, he was relieved when two atomic bombs ended the war in the Pacific.

“Years later, I felt qualms, but at the time we were happy. We’d seen a lot of planes taking off to bomb Japan, and we weren’t sure how these were different,” Smith says.

Married 64 years, he has three children, one recently deceased.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact staff writer Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Samuel Conte

CHAMPAIGN — On D-Day, Cpl. Samuel Conte’s landing ship went to the wrong part of the beach, and sent its troops off too …

Samuel Conte

CHAMPAIGN — On D-Day, Cpl. Samuel Conte’s landing ship went to the wrong part of the beach, and sent its troops off too …

Delmar E. Burgin

MONTICELLO — In World War II, Delmar E. Burgin served as a forward observer, directing artillery fire on the Germans, an …

Delmar E. Burgin

MONTICELLO — In World War II, Delmar E. Burgin served as a forward observer, directing artillery fire on the Germans, an …

Ronnie Turner-Winston

URBANA — Ronnie Turner-Winston considered her role as a chapel management specialist working with soldiers during Operat …

Ronnie Turner-Winston

URBANA — Ronnie Turner-Winston considered her role as a chapel management specialist working with soldiers during Operat …