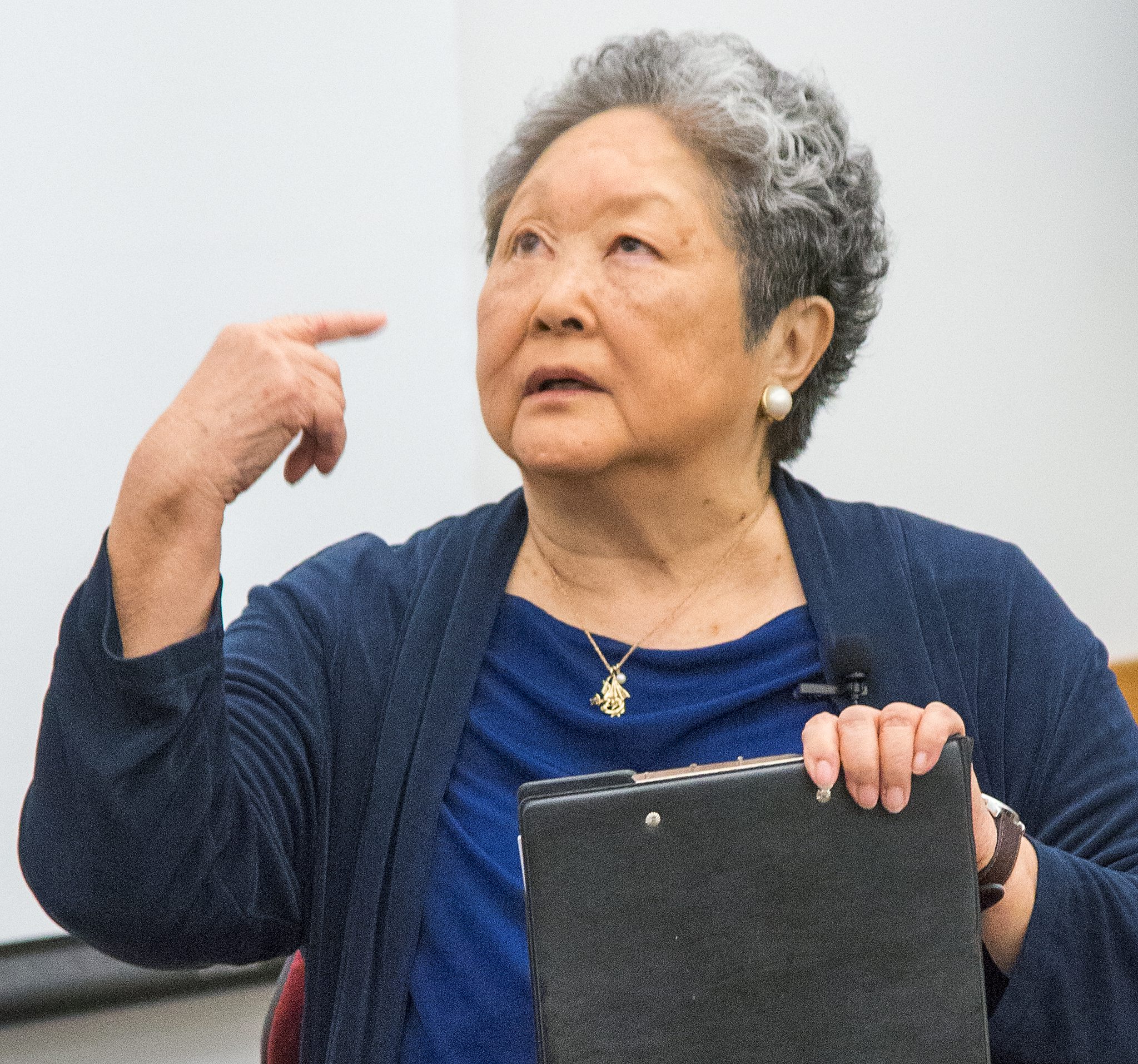

Yuki Llewellyn

By Paul Wood

Photo By Robin Scholz/The News-Gazette

Yuki Llewellyn knows what it’s like to grow up in an interment camp.

But she wasn’t held by the Germans or the Japanese. While most of the stories in this Monday series revolve around combat veterans, World War II also impacted the lives of noncombatants.

In fact, Llewellyn’s family is American, imprisoned by other Americans because they were of Japanese heritage, even though they were loyal to this country.

But the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 created a hysteria that was never matched by reaction to Nazi atrocities during the war.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, “relocating” Japanese-Americans, even those born in this country, to remote camps.

Already, Japanese born in Japan who came to this country were not allowed to be naturalized for decades and legally couldn’t own property under the Alien Land Law.

And yet they proudly fought for their new home. Nobody doubts the courage of the late Sen. Daniel Inouye, who fought in World War II in an infantry regiment.

He lost his right arm to a grenade wound in Italy and was one of the very few to earn the nation’s highest military award, the Medal of Honor.

Llewellyn and her mother, Los Angeles residents, spent three years interned at the Manzanar Assembly Center in California.

In total, the government ordered more than 110,000 people to leave their homes and detained them in remote, military-style camps. Manzanar War Relocation Center was one of 19 camps where Japanese-American citizens and resident Japanese aliens were incarcerated during World War II.

The federal government forced everyone of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast to, within days, try to take care of their homes, farms, businesses and possessions — often selling at a major loss.

Each family was assigned an identification number and loaded into transport to the camps.

Llewellyn, 78, had one blessing: She was too young to truly understand what was going on.

“I think it was terribly worse for the adults. My mother was 23. I could not have done what she did,” Llewellyn said.

She spoke last week at the Champaign Public Library about her experiences in the camp and on a children’s picture book called “Yuki Speaks Out,” being written by Karen Su, a UIC professor.

Llewellyn is a familiar name here, though she now lives in Missouri. She worked at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for 37 years, for 22 of them as assistant dean of students and director of registered organizations.

She was 3 when she arrived in Manzanar.

She remains an optimistic person. It showed at that young age.

“My memories were fun,” she said. “When you put a bunch of children close together, you make friends.”

“Honestly, kids don’t always know they’re being deprived until you tell them. In school, we celebrated every holiday known to man,” she said.

She was cut off in many ways from family traditions, but didn’t know that.

“The food at camp for adults was terrible. But the kids liked having potatoes and potatoes and potatoes,” Llewellyn said. “There was no rice at the beginning, and that was very strange for the parents.”

Undaunted, they grew their own Japanese-style staples.

“There were a lot of people with farming experience who said we’d like to start a garden,” she said.

“It was a wonderful change. I hadn’t know how much people were being deprived. We’d smash watermelons and eat them, a game kids will do, wherever they are.”

According to government statistics, 11,070 Japanese Americans were processed through Manzanar. From a peak of 10,046 in 1942, the population dropped to 6,000 by 1944.

“It was a very close neighborhood for us children,” Llewellyn said.

Upon leaving, the families were given $25 and a ticket, in their case to Cleveland, where the family had sponsors.

Decades after leaving Manzanar, and eventually moving to C-U, the educator is hopeful that things will change so that people respect each other’s differences.

“It’s still going on. The fact that people don’t come to terms properly with people who are different is scary, and I think there is now a growing momentum against certain people without cause,” she said. “I’m not into politics, but I am concerned.”

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Doug Robinson

SIDNEY — Back when Jimmy Carter was president, Doug Robinson had newly enlisted in the Navy, and was on a ship 3 miles o …

Doug Robinson

SIDNEY — Back when Jimmy Carter was president, Doug Robinson had newly enlisted in the Navy, and was on a ship 3 miles o …

Kenneth Dugan

PESOTUM — During the Korean War, Staff Sgt. Kenneth Dugan worked midnight shifts watching for “bogies,” unidentified pla …

Kenneth Dugan

PESOTUM — During the Korean War, Staff Sgt. Kenneth Dugan worked midnight shifts watching for “bogies,” unidentified pla …

Jill Knappenberger

CHAMPAIGN — In 100 years that have shown extreme courage in World War II and a lifetime of commitment to her church and …

Jill Knappenberger

CHAMPAIGN — In 100 years that have shown extreme courage in World War II and a lifetime of commitment to her church and …