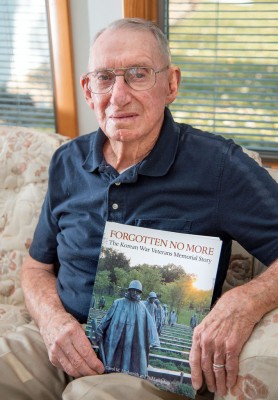

Thomas Labney

By Paul Wood

Photo By Stephen Haas

Thomas Labney, a 98-year-old U.S. Navy veteran who served on the USS Guam during World War II, talks about his service during an interview Friday, May 3, 2019, at his apartment in Savoy.

SAVOY — From freezing in Alaska to boiling just above the engine room in the humid South Pacific, Thomas Labney shipped out to fight the Japanese from one end of the Pacific to the other.

The Chicago native, 98, served in the Navy from January 1942, a month after the Pearl Harbor attack, to October 1945, a month after Japan’s formal surrender.

After trade school learning about sheet metal, he turned 21.

He went to Chicago City Hall, then open 24 hours, to enlist in the Marines because the enlistment lines were shorter there than at recruiting stations.

“We were going to kick their butts in six months,” he thought at the time.

The Marines office was closed, so he went across the hall to the Navy.

Labney got his basic training that month at Great Lakes, just north of Chicago. The early war was so hectic that six weeks’ basic training was shortened to three, he recalled.

That meant he never learned a basic skill.

“I never saw the swimming pool,” he said. “As a kid, I almost drowned in Lake Michigan, and I never did learn to swim.”

After all that hurrying about, the Navy was slow to put Labney into World War II.

On a bitterly cold Chicago day, he was sent to “warm and sunny San Diego.” He thought he’d be assigned to a destroyer there.

Instead, Labney found himself in several bases near San Francisco, including Treasure Island and Mare Island.

Labney was using his metal skills on submarine nets in San Francisco Bay, then went by train to Bremerton, Wash., a Marine base where the seaman was give bayonet training.

His skills built up, Labney then traveled to Adak Island in Alaska. He was stationed in the Aleutian Islands from 1943 to 1944, islands contested with the Japanese over who would control the sea lanes.

“We could hear the guns in the distance,” Labney remembered.

In the frigid waters, 30 of them built and maintained submarine and torpedo nets. They’d have five or six days to complete each mission, he said.

He thought the duty was over, when a lieutenant said, “I want two volunteers, you and you.”

They gave him a rifle and 100 rounds to serve a short time on the island of Attu with Army troops. Bulldozers dug trenches for the Japanese dead, and he guarded the supplies, including ammunition.

“It was the first time I was ever scared to death,” he said.

On leave, he got married.

Then he was assigned to a ship.

“Almost three years in the Navy without a ship,” he noted.

In January 1945, he was in a polar opposite, the South Pacific.

He served aboard the USS Guam as U.S. ships took Japanese-held islands one-by-one.

Labney worked in construction and repair, “making sure every door was tight and waterproof.”

His battle station was just above the boiler room, and the heat immediately made that apparent.

“You sweated, and your feet got really hot,” he recalled.

“It was a bad place to be if the boiler blew up, just about at the water line, so you could drown or be blown up.”

There were visible runways on the smaller islands, obvious threats from the air.

In March 1945, the leading USS Franklin was 50 miles from Japan, when a dive bomber dropped two bombs, each more than 500 pounds. More than 700 men were killed.

After Japan’s surrender, Labney was on the shakedown cruise of the Guam off the coast of Japan, as well as China and Korea.

With 44 points, he was one of the first to come home, in October 1945. He had a wife and 3-week-old daughter waiting for him. His mother had died a few months earlier.

The Labneys lived in Chicago until 1960, when they moved in Indiana.

The veteran has lived here since 2012.

Do you know a veteran who could share a story about military service? Contact Paul Wood at pwood@news-gazette.com.

Read more stories from local veterans:

Robert Alsop

CHAMPAIGN — At an outpost that could have been overrun any minute by the smallest of North Korean forces, Robert Alsop w …

Robert Alsop

CHAMPAIGN — At an outpost that could have been overrun any minute by the smallest of North Korean forces, Robert Alsop w …

Stanley Gilles

CHAMPAIGN — Even though Stanley Gilles worked three years for Illinois Bell as a lineman before he was drafted to Korea, …

Stanley Gilles

CHAMPAIGN — Even though Stanley Gilles worked three years for Illinois Bell as a lineman before he was drafted to Korea, …

Brent Blackwell

URBANA — In five deployments to Afghanistan, Staff Sgt. Brent Blackwell was a medic for an elite unit, the Army Rangers, …

Brent Blackwell

URBANA — In five deployments to Afghanistan, Staff Sgt. Brent Blackwell was a medic for an elite unit, the Army Rangers, …